Despite its primary purpose (as seen by the consuming world) as the cheapest available drug, coffee consumers have strong opinions on how it should taste. Specialty coffee especially prides itself on showcasing how different coffee can taste like, well, not coffee.

A change in style

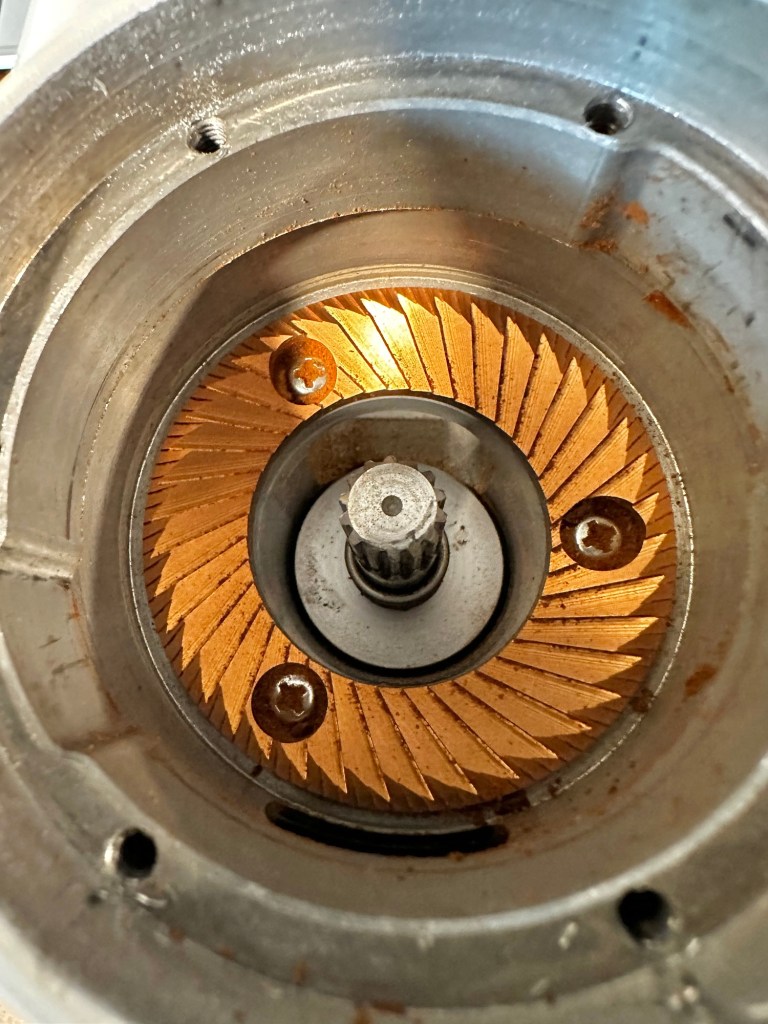

About decade and a half-ago, a certain spice grinder began being used as a coffee grinder. A very weird thing happens when you start using equipment that is radically different to what you’re used to, especially if it’s the kind that makes aspects of brewed coffee more perceivable. It’s hard to say which one happened first – did those who have the EK43 start roasting a little lighter because their darker roasts started showing aspects they didn’t enjoy, or those trying to roast a little lighter were vindicated by the joy brought about these radically different burrs in EK (or maybe even Forte). Maybe it was a mix of both. Whatever the reason, one suddenly had access to roasts that didn’t have specks of oil on the surface.

Lighter than light

My intent here is not to talk about light roasts of yore but rather light roasts as they stand today, although we’ll be revisiting the grinder and equipment aspect shortly. Some may claim that what we consider “Nordic light” was pioneered (or at least popularized) by Tim Wendelboe. To set a point of reference for this post, we’ll be considering Tim Wendelboe’s filter roasts at the “dark” end of the “light” spectrum. With that out of our way, and for those who continue to read, we’re going to dive into some points of view from both a philosophical and extraction perspective.

While there’s no objective definition of ultralight roasts based on colorimetry (which is its own rabbit hole), some common attributes based on prevalent discourse are roasts that are dropped prior to first crack, roasts lacking any form of burnt taint or astringency when extraction is pushed hard, roasts striving to showcase acidity over other aspects, and in general pursued by roasters in the industry tired of status quo in roasting philosophy and getting a chance to tell their point of view, or alternatively roasters who’re “outsiders” in the industry and had didn’t have the burden of legacy when trying to roast coffees they think they’ll enjoy themselves.

The burden of taste

There’s a lot of presumptions about ultralight roasts that aren’t necessarily true or alternatively vilified like the following:

- It’s too acidic

- It lacks body and/or texture

- It lacks complexity

- It’s underdeveloped

- It tastes like hay and peanuts

Let’s address these one at a time. The concept of acidity for example terrifies the very people who use terms like “showcasing origin” (whatever that means). Roasting ultralight ironically can result in a wide spectrum of perceived acidity. I like giving the example of Moodtrap Coffee (young kid based out of Singapore, aka Pradybeans) because it goes against several presumptions listed above. The acidity in Moodtrap’s coffees for example falls below the intensity that I prefer (I’m a sucker for intense perceived acidity), to the extent I like to sometimes brew his coffees at shorter ratios while targeting the same yield.

The biggest one that gets talked about ad nauseam is ultralight coffees lacking body and texture. Once again, you’ll be stunned at the amount of body Moodtrap can have in their coffees. Which should make one wonder, what is body if it’s not determined by roast level? To which I say, if you get your hands on Aviary’s 006 release by John Didier Trujillo, you would have been treated to a barely brown coffee which if you tasted blind would make you go, “Wow, this is coffee that tastes like coffee – sweet, rich, sticky, stone and cooked fruits, with all of these lingering in the aftertaste for days“. All of the said body perception was just by virtue of the green coffee, which in turn is a byproduct of varietal, microbiome, human intervention, logistics and a ton of other apsects. Oh and you can totally compensate for lack of body using various brewing techniques.

Complexity needs the shortest counterpoint – in my experience a well rendered ultralight coffee provides a complexity experience bar none. Keyword well rendered – ultralights will also suffer from roasting approaches that affect more developed roasts (e.g. baking).

The idea that something can be objectively underdeveloped is as ridiculous as the idea that something is “overdeveloped”. It’s valid to have concerns around and contention over a lightly roasted coffee’s extraction potential and dynamics (which we’ll address later), but much like brew recipes and equipment were traditionally developed around more developed roasts, modern equipment and rethinking of recipes have allowed for sufficiently extracting and evaluating ultralight roasts.

Finally, taste descriptors like “hay” and “peanuts” are as much if not more vilified than “bitter”, “astringent” and “burnt”. While I personally don’t prefer said notes, many I know are quite tolerant of bitter/astringent/burnt, much like many I know are quite tolerant of hay/peanuts/wheatgrass. So I find it ironic whenever one side throws shade at the other.

The burden of market

A lot of coffee consumption seems deeply rooted in nostalgia and habit. Customers have been served coffee for decades in ways that in that given day and age has been able to deliver caffeine to their bloodstreams in the most efficient manner possible. Indeed as a society, I’ll daresay that we’ve been trained longer to tolerate bitterness and astringency in coffee than we’ve been trained to tolerate taste aspects not traditionally associated with coffee (like fruits and florals). All this to say, it’s reasonable for cafes and roasters to cater to existing customer demands, and if opportunity allows, introduce them to newer ideas.

But, here we are, their customers, practically saying to them that ultralights are what we like and therefore need, and instead what we hear from them is that that’s not something they think is the right approach. They do sneak in the very condescending “it’s okay for you to like what you like”. And that my dear roasters, is gatekeeping at its best. Not only do you have the privilege of rendering roasts that does justice to a farmer’s crop, and thus have power over how their product gets perceived, you also get to dictate what the customer wants.

There’s also a prevailing myth that roasting ultralight is what beginner roasters start out with till they realize that the “right” way to do it is to develop it more. Coulter Sunderman (H&S) only recently shifted to doing ultralight roasts after having vied to do so for several years but operational restrictions not allowing for it till a couple of years ago. Christopher Feran, whose roasts I’ve consumed since his time at Phoenix, uses Aviary to showcase his taste preference in coffees through how he roasts at Aviary. They’ve arguably consumed and enabled gallons if not barrels of more developed brews, but yet choose to render coffees ultralight. Much like “specialty coffee” looked to do things differently than just adding milk to coffee (even though milk drinks are 95% of their sales), a newer generation of roasters and customers is trying to tell the industry that that other 5% doesn’t need the dogma that gets thrown about.

Roasters – there’s a new market and you’re missing out on it.

Why so popular now?

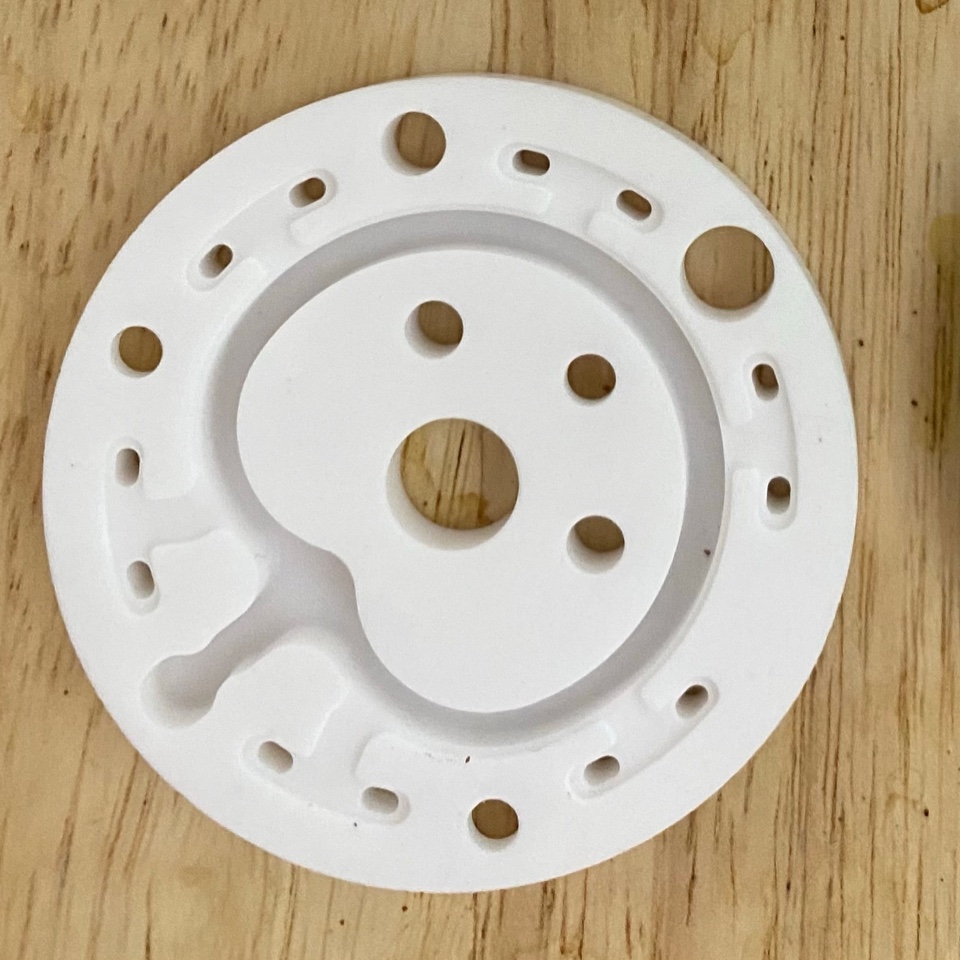

The last four years have seen an explosion in grinders that have allowed consumers to experience the same or better flavor separation than what EK43 brought about when it started making waves, but have done so at a fraction of the price of an EK. With handgrinders like 1Zpresso Q2 and ZP6 allowing for filter brews at home that were at best considered mythical outside of cafes a decade ago, and electric grinders like Turin DF64 and Fellow Ode retrofitted with a variety of aftermarket burrs (usually SSP) allowing for both filter and espresso, not only were consumers now able to taste and brew coffee in a way they hadn’t before, but were also able to notice that ultralight roasts could be pushed harder in terms of extraction without hitting astringency. Alternatively, any aspects of roasts that customers would have otherwise put up with due to less clinical grinder profiles, were now laid bare, with the highs being very high, and the lows making them regret spending $30 on 250g of coffee. Carl Broughton (aka flow on EAF/BANA) lays out this phenomenon very well in his post on what’s caused “the shift”.

I feel like roasters are yet to realize that the $150-200 that folks would spend on a Baratza Encore is instead being spent on equipment that’s probably putting their QC to shame.

But it’s hard to extract

This is probably the most interesting one to navigate and worth having an intricate discussion about. I will navigate this issue for filter and espresso separately. Filter is probably the less controversial one due to maybe a gazillion brew recipes available on the interweb that allow for anywhere between intentional low extraction and unintentional high extraction. As opposed to how things were a decade ago, more people are now less afraid of a V60, there’s communities built around users who mainly use something like an Orea, Cafec has filters that can do anything from clog a brew as soon as you pour water or make you struggle to slow a brew down at very fine grind sizes, and folks have figured out how to fit conical filters in flat bottom brewers for more accessibility. Folks have ways to agitate so much that the filter will ask for mercy or alternatively agitate so little that Ray Murakawa would be proud. There’s online communities like EAF where if you can’t figure out how to brew in a way to get a result you like, at least ten people will give you possible solutions to get there (after, of course, using the “skill issue” emote). Having communities like these means that unlike in the past, most folks know how to get around a taste component they don’t like, so blaming the roaster becomes more justifiable. This also means that folks who don’t like certain aspects of a roast now have a way to learn from others what roasters they can buy from to avoid certain tasting notes or roasting styles.

Espresso is where it becomes a complicated discussion. What is espresso is in itself a very subjective thing. Some don’t budge from a 1:2 ratio, others find comfort in 1:3, the rest wake up not knowing what setting their grinder is at and pull a 1:10. Many love their 30 seconds or gtfo dogma, some are very much fine with a minute long shot, while the rest are terrified to go beyond fifteen seconds. There is however some history of light roast espresso that needs to be revisited before we come to ultralights. At a time when equipment was geared toward 9 bar extractions and burrs were designed to generate fines to both reach such a pressure and also potentially account for misalignment, getting sufficient yield within the parameters of what was considered espresso using a lightly roasted coffee became a problem. To quote Mat North, “We suddenly realized maybe we should be passing more water through the puck”. While this was indeed a solid option ten years ago, times have changed. Consumers now have access to modern burrsets that allows them to extract in 12 seconds what traditional burrs did in 30. Alternatively they have access to machines that can let them pull shots for longer than 30 seconds or by restricting pressure to no more than 2 bar (even when the machine can do more) at very humble pricepoints. Once again, the consumer has many ways to get around a roast component, so a lot of them are preferring to purchase “filter” roast offerings from a given roaster even though they’re mostly brewing espresso. And I can guarantee you we make shots that don’t taste like water. Indeed many of us live for the incredible body, sweetness, flavor separation, acidity and overall taste bombs that make you dream about these shots for hours on end. These extract quite easily more than 22% at 1:2. In twelve seconds. With ultralight roasts.

It is indeed getting harder to believe that roasting darker is more “approachable”. And as for the question of milk drinks, I do wonder how the market is for milk drinks that are inherently sweet, fruity, potentially floral, with an aftertaste that makes you want to chug another one right away.

Eight weeks?

Higher shelf stability is arguably a dream that every roaster and consumer shares. Indeed when ultralight roasters these days say “don’t you dare fucking open that bag for four weeks”, it’s something that they themselves have had a reckoning with. This, of course, also means that these bags can be forgotten about and then rediscovered three months later in the cabinet, just when you thought you’d run out of coffee. This also reduces the potential for needing freezer storage with proper planning. Potential downsides seem to be the effort spent by roasters on educating newer customers that “fresh is worse” and consumers not being able to enjoy a coffee at its fullest potential sooner than four weeks (sometimes 6-8 if doing espresso). I do empathize with roasters having to adapt their QC/cupping process to be able to roast and tweak subsequent profiles without the coffee reaching peak age. But somehow roasters who execute ultralight coffees well seem to have mastered this process (Coulter’s water doesn’t even boil at 100°C and yet he almost has the same findings in a roast that I do).

Must be the roasting machine or water

Admittedly a bunch of ultralight roasters are roasting on machines like Stronghold, which seem to allow for very even development at lighter roast levels with arguably more ease. However, many ultralight roasters are using legacy machines like Probats and Diedrichs. (There’s a running joke that H&S should not be able to pull off the roasts he does on his IR-12).

Similarly, even though the phenomenon of exploring water chemistry has seen an exponential increase in adoption among consumers, in my opinion it’s not an absolute dealbreaker to not know much about one’s water hardness and alkalinity. If anything, products like Lotus Drops have allowed folks to explore brewing with distilled or RO water and remineralize to desired levels of hardness and alkalinity depending on coffee and grinder. In other words, it’s quite trivial these days to adjust water chemistry on the go to help dial-in roasted coffees to taste, to the extent that it’s quite possible to make more developed roasts not taste as much of bitterness or astringency. And yet we choose ultralights because a lot of them don’t necessitate adding hardness or alkalinity to an extent that it drowns out preferred aspects of a coffee.

Not problem-free

There are, however, genuine concerns that I have about roasting ultralight. Many roasters having realized that this is a new market they can tap into, are roasting light for the sake of roasting light, resulting in unremarkable roasts from stellar green. Many find it difficult to avoid baking their roasts, while others manage to sneak astringency in even at ultralight levels of roasting. One could even argue that if times were any different, say like a decade ago, they would have made similar mistakes in execution, just at a different roast level. Consistency is hard, even when roasting ultralight, but roasters, you still have the most power.

You’re saying we’ve been doing it wrong?

Many folks I’ve learned from in the coffee industry have been around for decades now. Many are skeptical of the need for change, which is justified if their exposure and careers are centered around commercial environments. After all, they’ve been there, done that. Then why is it that there’s a whole new market born out of dissatisfaction with existing roasting approaches and quality? Is inertia the answer for such a young industry that has barely scratched the surface of knowledge when it comes to pretty much any aspect of coffee? Is it possible that the consumers they dreamed of, ones who live paycheck to paycheck but still spend on expensive roasts because they find it worth the experience, are finally here (ready with the tools to brew no less), and roasters aren’t ready for them?

Acknowledgements

Coulter Sunderman: For being the most humble yet consistent roaster to bring joy to ultralight drinkers

Christopher Feran: For finally delivering on his vision of roasting through Aviary

Andrew Sinclair: For engaging with the coffee community, sharing his learnings at no cost, and keeping it real with late night rants

Carl Broughton (Flow): For getting the conversation started about ultralights and sharing recommendations for ultralights

If you’ve enjoyed this post, consider supporting amazing coffee folks doing non-coffee things at Pollinator Project.

Consider subscribing to keep your pocket full of coffee science.

Leave a reply to pocketsciencecoffee Cancel reply